The Aristocats (1970)

Plot Overview

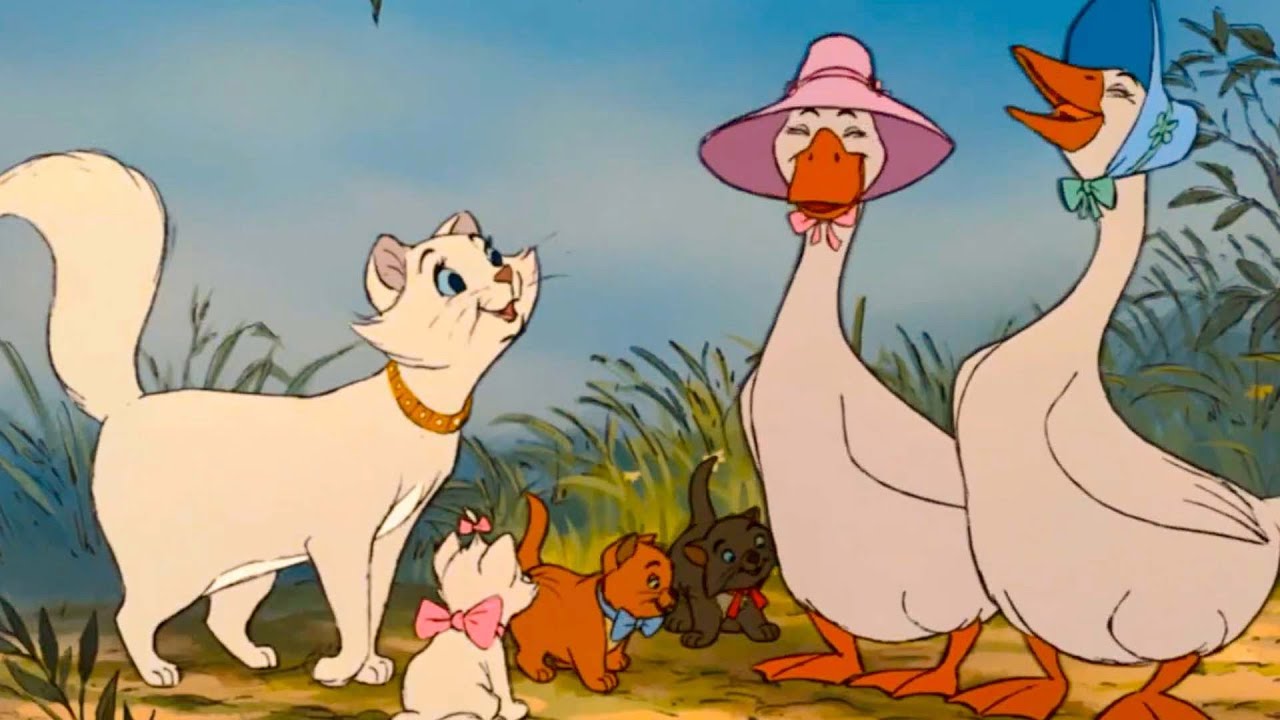

The Aristocats whisks us to 1910 Paris, where Madame Adelaide Bonfamille (voiced by Hermione Baddeley), a retired opera diva, lives in aristocratic splendor with her beloved cats: the elegant Duchess (Eva Gabor) and her rambunctious kittens, Marie (Liz English), Toulouse (Gary Dubin), and Berlioz (Dean Clark). The film opens with Madame drafting her will, leaving her fortune to the cats—her only family—before it passes to her loyal butler, Edgar Balthazar (Roddy Maude-Roxby). Overhearing this, Edgar, a balding, bumbling servant with a taste for luxury, decides he won’t wait decades for his share. His solution: kidnap the cats and dump them in the countryside, ensuring he inherits first.

Edgar’s scheme kicks off with a slapstick twist—he laces the cats’ cream with sleeping pills, but a scuffle with alley cats Napoleon (Pat Buttram) and Lafayette (George Lindsey) derails his plan. The drugged felines are bundled into a basket and abandoned by the Seine, waking dazed as Edgar flees on his motorcycle-sidecar combo. Stranded, Duchess and her kittens meet Thomas O’Malley (Phil Harris), a streetwise alley cat with a smooth baritone and a knack for survival. Smitten by Duchess’s grace—and charmed by the kids—O’Malley offers to guide them back to Paris, sparking a jazzy odyssey across France.

Their journey is a patchwork of misadventures. They hitch a ride on a milk truck, dodge Edgar’s clumsy pursuits, and crash a goose sisters’ (Monica Evans and Carole Shelley) waddle through the countryside—complete with a tipsy Uncle Waldo (Bill Thompson) fleeing a chef’s oven. In Paris, O’Malley introduces them to his scat-cat crew, led by Scat Cat (Scatman Crothers), whose “Everybody Wants to Be a Cat” jam session lights up a derelict mansion. Edgar, meanwhile, scrambles to cover his tracks—retrieving the cats’ basket from the river only to stumble into Napoleon and Lafayette again, losing his hat and umbrella in a barnyard chase.

The climax unfolds back at Madame’s mansion. Edgar traps the cats in a sack for a second disposal—this time to Timbuktu via mail—but O’Malley rallies the alley cats for a rescue. A chaotic brawl ensues—Scat Cat’s trumpet blares, Roquefort the mouse (Sterling Holloway) bites Edgar’s ankle, and Toulouse’s paint flings like artillery—ending with Edgar stuffed into his own trunk, shipped off as Madame obliviously mourns her pets. The film closes with a purr-fect resolution: O’Malley joins the family, Madame rewrites her will to fund a cat sanctuary, and the gang belts out a reprise of their jazzy anthem, cementing their aristocratic happily-ever-after.

The script, credited to a team including Ken Anderson and Larry Clemmons, is a lighthearted romp—less intricate than GoodFellas’ saga or Terminator 3’s stakes, but brimming with Disney’s post-Walt whimsy. At 78 minutes, it’s a breezy tale of class, loyalty, and feline flair, dodging heavy morals for a toe-tapping escape.

Character Dynamics and Performances

Duchess, voiced by Eva Gabor, is the film’s refined soul—a single mother balancing poise and panic with Hungarian-accented charm. Gabor’s lilting tones—“Thomas, this is no time for fun”—lend Duchess a maternal elegance, her warmth shining when she soothes Marie or flirts with O’Malley. Phil Harris’s Thomas O’Malley is her roguish foil, a gravelly-voiced charmer echoing his Jungle Book Baloo. Harris belts “The Aristocats” theme with swagger, his riffing with the kittens—teaching Toulouse to growl or calming Berlioz’s nerves—building a scruffy-stepdad vibe that’s the emotional core.

The kittens—Marie, Toulouse, and Berlioz—are a trio of mischief and heart. Liz English’s Marie sings “Scales and Arpeggios” with prim innocence, her “I’m a lady” quips clashing adorably with her tumbles. Gary Dubin’s Toulouse growls like a pint-sized tiger, his painterly bravado sparking laughs, while Dean Clark’s Berlioz, the shy pianist, adds quiet pluck—Clark’s soft “Mama!” tugs strings. Their interplay with O’Malley—pestering him like adopted pups—grounds the romance in family, a dynamic that’s pure Disney magic.

Roddy Maude-Roxby’s Edgar Balthazar is a bumbling villain, less menacing than comical—his nasal whining and muttered schemes (“I’ll be rich!”) make him a hapless antagonist, not a terror. Maude-Roxby’s pratfalls—tripping over cats, outwitted by dogs—steal scenes, though he lacks the gravitas of a Terminator foe. Scatman Crothers’s Scat Cat leads the alley gang with jazzy gusto—his scat-singing and trumpet riffs in “Everybody Wants to Be a Cat” electrify, a counterpoint to Edgar’s stuffiness. Pat Buttram and George Lindsey’s Napoleon and Lafayette, the hound duo, bicker like a rustic Laurel and Hardy—Buttram’s “I’m the leader!” gruffness bouncing off Lindsey’s dopey drawl—adding barnyard chaos.

The ensemble thrives on contrast—Duchess’s polish versus O’Malley’s grit, Edgar’s greed clashing with the cats’ loyalty. Voices like Sterling Holloway’s squeaky Roquefort or Hermione Baddeley’s dotty Madame round out a cast that’s less about depth than delight, their interplay a jazzy jam session of purrs and puns.

Direction and Visual Style

Wolfgang Reitherman, a Disney veteran

post-Walt’s 1966 death, directs The Aristocats with a playful, relaxed hand—less ambitious than Mission: Cross’s action or GoodFellas’ intensity, but rich in charm. Animator Ken Anderson’s Parisian backdrop glows with hand-drawn whimsy—cobblestone streets, pastel rooftops, and the Seine’s shimmer evoke a storybook 1910, not a gritty realism. The countryside—rolling fields, rickety bridges—adds rustic flair, though its Xeroxed lines (a cost-saving trick from 101 Dalmatians) lend a sketchy edge, softer than Sleeping Beauty’s polish.

The animation leans on character—Duchess’s graceful sashay, O’Malley’s loping strut, and the kittens’ tumbling antics burst with personality. Action is light but lively—Edgar’s motorcycle chase with Napoleon and Lafayette spins into cartoon chaos, dogs snapping at tires, while the mansion brawl pops with paint splashes and scat riffs. Reitherman keeps it simple—nothing rivals Terminator 3’s crane crash—but the slapstick flows, paced for kids without dragging.

George Bruns’s score swings with jazz—Maurice Chevalier’s “The Aristocats” opener sets a toe-tapping tone, while the Sherman Brothers’ “Scales and Arpeggios” and “Thomas O’Malley Cat” keep it bouncy. The “Everybody Wants to Be a Cat” finale, with Floyd Huddleston and Al Rinker’s lyrics, is a psychedelic romp—neon hues swirl as cats jam, a rare ‘70s flourish in Disney’s canon. Sound design—meows, honks, Edgar’s sputters—adds texture, though it’s no sonic marvel.

Reitherman’s direction embraces a post-Walt shift—less epic than Cinderella, more like Jungle Book’s looseness—focusing on fun over grandeur. Backgrounds dazzle (Madame’s mansion drips opulence), but the Xerox process shows wear—lines wobble, colors bleed slightly. It’s a cozy, unpretentious tale, its visual warmth a hug from a bygone Disney era.

Overall Impact and Reception

The Aristocats purred into 1970 theaters, grossing $55.6 million worldwide ($26 million domestic) on a $4 million budget—a hit, though no Lion King juggernaut (adjusted, it’s ~$380 million today). Critically, it’s a middling gem—73% on Rotten Tomatoes (retroactive)—praised for charm but dinged as “minor Disney” (Variety’s “pleasant fluff”). Opening weekend earned $3.2 million, buoyed by Christmas crowds, cementing its family appeal post-Walt.

Its impact is nostalgic, not seismic—released amid Nixon’s America and Disney’s post-founder drift, it’s a comfort blanket, not a revolution like GoodFellas. For 1970 kids, it was a jazzy escape—O’Malley’s cool, Marie’s pluck, and that scat finale stuck, spawning a 1987 TV special and endless VHS reruns. Historically, it’s transitional—between Disney’s Golden Age and ‘80s revival—lacking Sleeping Beauty’s artistry or Little Mermaid’s heft, but its feline spin on class (alley vs. aristocrat) endures, echoed in Oliver & Company.

Posts on X in 2025 call it “underrated” or “pure joy”—its songs (“Everybody Wants to Be a Cat” streams big on Spotify) and cat-centric whimsy resonate with pet lovers, though some lament “dated animation” or “thin plot.” Strengths—voice cast sparkle, jazz bounce—outweigh flaws: a slight story, Edgar’s weak menace, Xeroxed roughness. It nabbed no Oscars (unlike Lion King’s haul), but its legacy purrs on—#64 on Animation World Network’s “Top 100 Animated Films,” a cozy classic that doesn’t roar but charms with a wink and a whiskers’ twitch.

The Aristocats is Disney lite—a feline frolic that trades depth for delight, its scat-cat soul a timeless purr in a louder cinematic world.